The title already hints at it: My time in the Central American countries of El Salvador, Honduras, and Nicaragua wasn’t exactly the most pleasant, yet there was still plenty of exciting things to observe and experience.

Hazy landscapes and frequently patched roads – Bienvenidos a Centroamérica!

At the beginning of May, I travelled from the highlands of Guatemala and took the Hachadura border crossing in the lowlands of El Salvador. The combination of the tropical lowlands and the time of year meant extreme heat paired with extremely high humidity – the rainy season was just around the corner. Even just sitting down made you sticky from the constant sweat; if you could take a shower, you were drenched in sweat again shortly afterwards and there was no serious cooling at night either. When camping, of course, I only pitched the inner tent, which consisted of lots of mesh, but even that was like a greenhouse. But I couldn’t do without a tent, because otherwise the mosquitoes would eat you up, and in this region they like to have a bit of dengue in their luggage. Or perhaps Mr and Mrs Scorpion would drop by for a little ‘detour’. In the accommodation, there were always numerous ventilators humming all the time. In the hostel dormitories, each bed had its own fan – but that only helped to a limited extent.

In the second half of May, the rainy season slowly set in, which meant torrential downpours including thunderstorms. From then on, I had to find a roof to sleep under every afternoon. But somehow it almost always worked, because Central America is extremely densely populated. And where there are fewer people, everything is fenced in with spiky wire so that there is hardly any chance of wild camping, so I ended up looking for a place to sleep somewhere in populated areas and asked for a roof or took accommodation straight away. However, wild camping would not necessarily have been the smartest idea in this area due to the security situation. Unfortunately, opportunist thefts or robberies for socio-economic reasons are not uncommon in these countries.

Rubbish, scorpions and the typical hustle and bustle.

Central America is a relatively narrow strip between the Caribbean Sea and the Pacific Ocean, there are not so many route options and due to the dense population you can rarely escape the hustle and bustle. There is a lot of honking on the roads, a lot of fumes and loud music everywhere – if you are looking for peace and quiet, you might find it on the island of Ometepe in Nicaragua, but otherwise you should be a bit resistant to the constant stream of stimuli if you want to stay there for any length of time.

El Salvador

At the beginning of my cycle tour, El Salvador was still considered one of the most dangerous countries in the world, with an incredibly high murder rate. Back then, I wouldn’t have dared set foot in the country. However, the situation has changed completely under President Nayib Bukele since March 2022. He declared a state of emergency in the country and stepped up the control of public areas by police and military forces to an extremely high level, which, among other things, enabled over 80,000 gang members to be arrested. The murder rate is now below that of Canada, which means that El Salvador’s security situation can now easily be compared with that of Western countries. Before all these measures, public life in the smallest of the Central American states must have been quite restricted. The population hardly dared to leave their own four walls, and from the late afternoon hours the streets must have been as deserted as they are today in the coastal towns of Ecuador, for example, where gangs control public life.

However, I didn’t notice anything of this restricted, secluded life – everywhere in El Salvador was extremely busy and even after dark the towns were far from dead. I often saw groups of three or four heavily armed police officers or soldiers patrolling the streets on foot – the guarantors of current security. Many of the El Salvadorians greeted me in an extremely friendly manner and were often interested in a chat – my guess is that before the current government’s measures, there probably weren’t that many tourists in the country and probably not in the corners of the country that a touring cyclist passes through when crossing the country from north to south. However, this newfound security also comes at a certain price: the state of emergency and other measures are constantly being extended, although the legal basis for this is disputed. In the case of arrests, those arrested have little or no opportunity for legal assistance, which can make these actions rather arbitrary. I have heard critical voices from time to time, especially from residents of other Latin American countries. Nevertheless, the inhabitants of El Salvador can now feel safe from the gangs for the time being; the desire to emigrate seems to have decreased somewhat, even if around half of the inhabitants still live below the poverty line. In any case, I felt safe and was able to continue my journey south by land.

In the streets of Santa Ana.

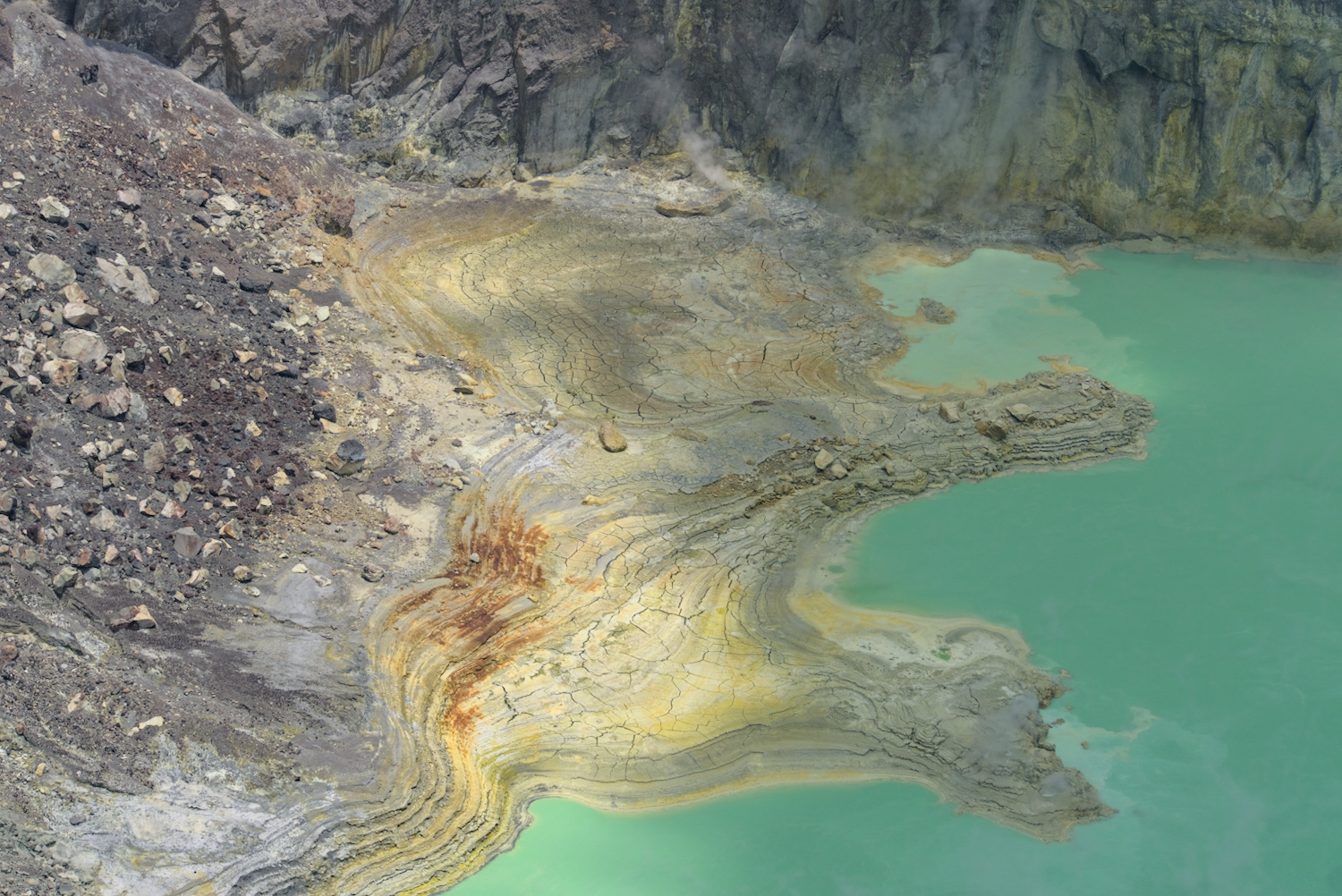

After it was so incredibly hot on the Pacific coast, I headed for the mountains again. I stayed in a hostel in the town of Santa Ana for a few days to organise a few things online and also to tackle one of El Salvador’s typical tourist activities: A hike to the crater rim of the Ilamatepec volcano to enjoy the view from this 2381 metre high mountain of the surrounding area as well as into the crater itself. Unfortunately, it wasn’t quite as impressive as I had imagined. On the one hand, the clouds didn’t quite play nice and mostly denied far-reaching views of the surrounding area, and on the other, it really was one of those mass tourism attractions. To get to the starting point of the hiking trail, I was able to simply take a chicken bus, which was completely crammed with locals apart from a few tourists – an authentic experience and quite nice so far. Once I arrived at the starting point of the trail, however, it was compulsory to pay a guide and hike up to the crater with him in a group of other tourists – the moment when the trip became annoying. The guide himself actually just walked ahead of the group without explaining anything – but we hikers couldn’t get lost on the absolutely clear path with no turn-offs. My group was quite small with 13 or 14 hikers, as we had all come to the starting point on our own. However, there were much larger groups at the start, who had travelled by coach from wherever. In addition to the guides and excursionists, two policemen armed with rifles were strutting around the volcano – a rather unusual sight for excursions into pure nature. Even though I didn’t have a great view and couldn’t enjoy the scenery on my own, there were still a few beautiful views of the vegetation at Ilamatepec and ultimately also of the turquoise-coloured acidic crater lake, including a few olfactory experiences from the rising sulphur oxide vapours.

On the way at Ilamatepec.

It was nice and quiet again on the way towards Suchitoto. I cycled along wonderfully small roads with hardly any traffic into this small colonial village and then a little further on to a private viewpoint above the dammed Rio Lempas. Private does not mean that it was mine – it was in fact a private property, tactically located for a viewpoint, where the owner grants access to the view for a small entrance fee. In the fenced-in areas of Latin America, this is a typical type of ‘’business‘’, sometimes there is also a small restaurant or kiosk. In any case, I was allowed to pitch my tent there and had the whole site to myself as dusk fell. But it wasn’t just the brilliant view of the reservoir that was worth the three dollars – there was also a dried-up waterfall over a basalt column cliff on the same property, which was quite photogenic even without water thanks to the rock formation.

The next morning, I kept a close eye on the odometer, as I was now due to break the 40,075 kilometre mark – the distance that corresponds to a circumnavigation of the earth along its greatest extent around the equator. Even though it was just a number and instead of going round the world once, I only drew a strangely shaped, partially convoluted line on the map somewhere, I was delighted with this small milestone.

Once I arrived back on the hot Pacific coast, it was time to try something new. As often as I had heard that the Bomberos in Latin American countries should be particularly open to cyclists and offer them free accommodation, I had never tried it in the past four months. In the small town of Usulután, I went to a fire station for the first time, introduced myself and asked for a dry and safe place to spend the night. Without asking any further questions, they invited me in and immediately showed me a room with large fans where I could simply roll out my sleeping mat. Showers, toilets, power sockets – everything was at my disposal. I was completely perplexed by this open hospitality, but couldn’t really let it sink in, as I wasn’t the only bike traveller on site. Rhian and Chris from the UK were already there and of course there was plenty to talk about. It wasn’t their first time at the Bomberos, as they had already stayed at several other fire stations before.

It wasn’t far to the next border now, Rhian and Chris’ route would also continue south and so we decided to cycle together through Honduras to Nicaragua – not without good reason.

Honduras

In 2015, Honduras was the second country with the highest murder rate per inhabitant, just behind El Salvador. President Xiomara Castro, who was elected in 2022, has declared a state of emergency, restricting civil rights and allowing the police and military to be increasingly deployed against gangs. She also had her predecessor Juan Orlando Hernández extradited to the USA, who was allegedly involved in drug smuggling during his time in office. Despite these efforts, gang violence in the country has not yet been significantly reduced – Honduras is still considered one of the most dangerous countries in Latin America. The centres of gang violence are located in the more densely populated north of the country, while the relatively small section along the Pacific is less populated and is considered safer.

Even with this superficial insight into the security situation in Honduras, it is clear that the Central American country is currently not a long-awaited destination for cycle travellers. The decision to cycle together from El Salvador to Nicaragua via the shortest route through Honduras was therefore an obvious one for the three of us. In total, there were only 130 kilometres of flat land on the Panamericana between the two border crossings – a route that many cyclists take through the country and where there were no known safety issues. Planning for the rainy season, we wanted to cycle the section in two and a half days and spend the night at the Red Cross in the towns of Nacaome and Choluteca. Another cyclist had given me exactly this tip, having previously travelled in the opposite direction. And if you’re expecting any scary horror stories about my time in Honduras, you’re wrong, because everything worked out as planned. In Choluteca, we camped under a roof at the Red Cross, but still had to struggle with the masses of water from the tropical downpour in the evening. In Nacaome, we were given an air-conditioned shared room all to ourselves at the Red Cross – what a luxury! The only negative thing I took away from the country was a moderate case of food poisoning – probably due to a bad coconut from a street vendor.

Nicaragua

In good company with Rhian and Chris.

On the very day we were due to cross from Honduras into Nicaragua, I started to feel unwell. At lunchtime in the village just before the border, instead of eating something, I took out my fever thermometer – I was afraid I might have caught dengue fever, but my body temperature was normal. It wasn’t until later that evening in the toilet that I found out what it probably was. To be honest, at that moment I was pretty happy that it was ‘only’ food poisoning.

The annoying entry procedure to Nicaragua was definitely not what my body was longing for in this state. Even in a healthy state, this is a process that is better avoided. Even before reaching the actual immigration building, there were checks, followed by a wait of over an hour until the immigration card was filled out with a carbon copy, the same data entered into the computer again and then the entry fee was collected. The latter was of course in dollars, although the local currency is Córdoba – a border like this is quite practical for obtaining more stable foreign currency. Once this bureaucratic hassle was over, we had to unload our luggage from the bikes to run it through an X-ray machine. Of the 41 countries I visited on this trip, this was otherwise only necessary in Iran and at one of the five border crossings I passed through in Turkey. At a subsequent final check, we again had to hand in some paperwork. After more than two hours, we were finally inside.

With its economic situation, Nicaragua doesn’t really need to protect itself from an invasion of Western tourists – it’s one of the poorest countries I’ve ever travelled to. But somehow the border behaviour of totalitarian regimes is always a little more intense. Because Nicaragua is ultimately just that: a totalitarian one-party state, or at least that’s what the Ortega regime has turned the country into with the 2022 ‘elections’ – an election result in which 153 out of 153 municipalities go to the FSLN party looks very Russian.

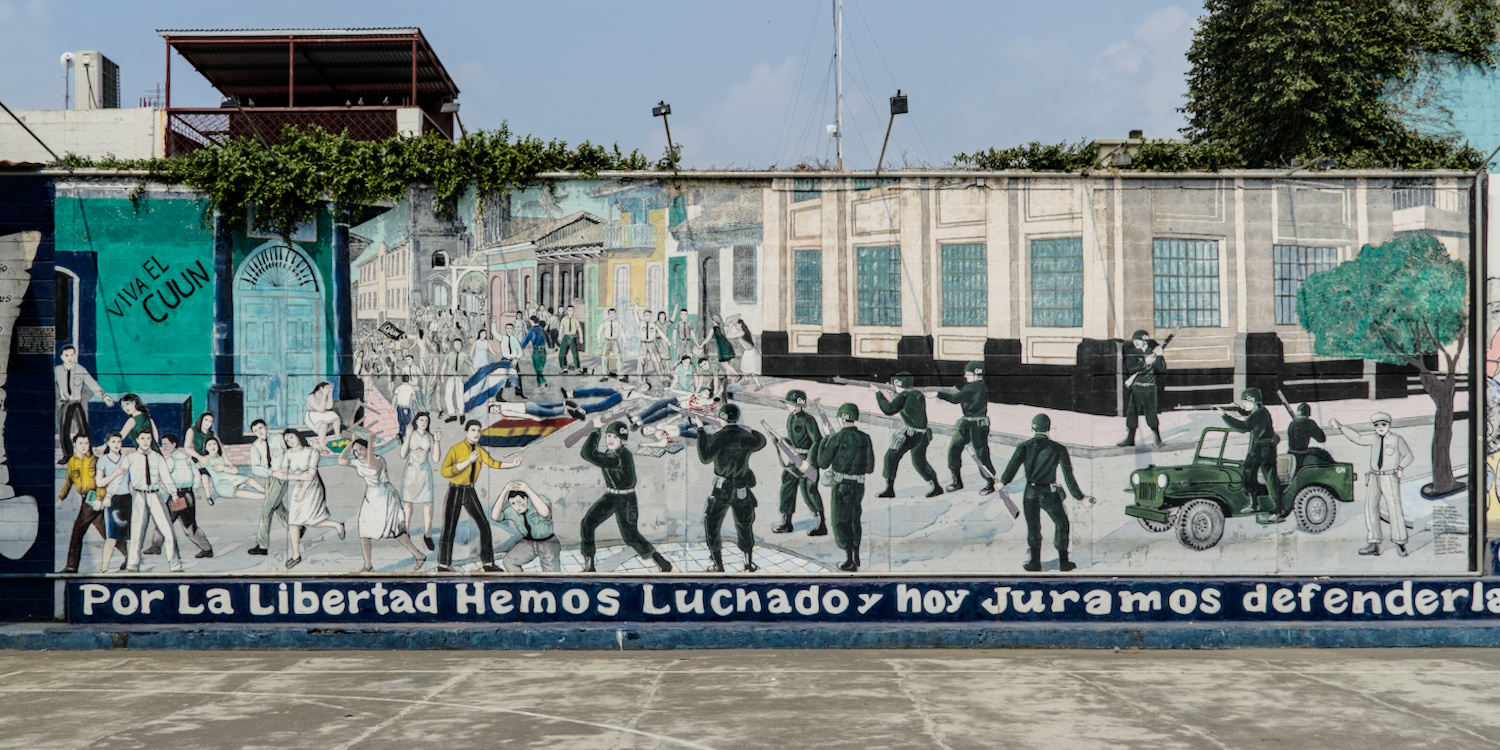

The FSLN party is omnipresent.

The whole country is plastered with FSLN propaganda. Flags, murals, heroic war memorials, an entire ‘boulevard’ in Leon decorated with the history of the FSLN or the neatly maintained and guarded monument in the capital Managua next to the National Palace, directly opposite the cathedral, which has not yet been rebuilt due to a lack of funds since the 1972 earthquake. The FSLN party emerged from the Sandinista revolutionary movement in 1978, which overthrew the then Somoza dictatorship. The country has therefore been ruled by authoritarian regimes for generations, has been repeatedly subjected to sanctions by the USA as a result and is now completely impoverished.

Poor roads, primitive huts and buildings in need of renovation are nothing unusual in Central America, but in Nicaragua the proportion was quite high. There were always horse-drawn carts to be seen on the roads, once even an oxcart – not as a tourist attraction, but as the everyday means of transport for the poorest of Nicaraguans. One of the fire stations where I spent the night looked so run-down to me as if the firefighters had been given the site of an industrial ruin – and they now had to work there and live there with their children. This sad picture was further emphasised by the prevailing drought in the country. Pastureland was scorched by the sun, it was dusty and the cattle were rattling thin. It is normal for it to be particularly dry in this region just before the rainy season, but the rain was already a little late and the situation for the people was a little more tense.

Nicaragua is shaken by poverty.

Apart from the arid pasture landscapes, the country with its countless volcanoes had something to offer visually. It feels like one volcano follows the next along the rather flat Pacific coast, with each one rising out of the plain like a picture-book cone. There are picturesque crater lakes at some of the extinct volcanoes, whereby the two huge lakes ‘Lago Xolotlán’ and ‘Lago Nicaragua’ with their volcanic islands are an absolute feast for the eyes.

Volcanoes upon volcanoes, crater lakes and tropical trees.

The largest of these islands is Ometepe and it is also located in the largest lake in Central America, Lago Nicaragua. Viewed from above, the island can be roughly described as an eight, as it consists of two conical volcanoes – the active Conceptión volcano and the extinct Maderas volcano. It takes a good hour to take the ferry from San Jorge to the village of Moyogalapa and then you find yourself in a different world. It is much greener and more densely forested than on the mainland, the birdsong is much more distinctive, there are howler monkeys and supposedly caimans to marvel at. On Ometepe, the clocks go slower, there is an absolute island feeling, if not a hippy vibe. The island is rightly a small tourist magnet, but apart from the ferry crossing, I didn’t notice much of the other tourists. There are so many hostels that it’s easy to get lost – but perhaps things are a little different in the high season. Due to time constraints, I only cycled around the Conceptión volcano. In hindsight, I should have stayed on the island a little longer and visited the other half too – somehow it was one of the cosiest and most unspoilt spots in Central America.

On the road on Ometepe.

Back on the mainland, it was not far to the next border and although the exit was a little quicker, the ‘experience’ was just as modest as the entry. The border official only wanted to be paid in dollars, naturally had no change and then of course the luggage had to be x-rayed again. Entering Costa Rica, on the other hand, was super quick, the officials were extremely friendly and simply waved me through at customs.

Travel time: May 2024

Sources:

Leave a Reply